What is Docker?

Over the past one year, I posted a couple of blogs on Docker. I am not fully convinced that I have fully grasped or explained what Docker is. This is another attempt to fully understand and explain the basic concepts of Docker and the evolution of virtualization.

Pre-Virtualization

Before the advent of virtualization, servers with one operating system (OS) per machine would run one application. Running multiple applications on the same physical machine would often create resource conflict. The safest option was to run one application per machine. As a result, the number of expensive but servers would multiply but without providing proportional value in return. In some estimate, 88% of the server resources were un-utilized. This acted as a fertile ground for innovation in the field of server virtualization to reduce the infrastructure cost and increase flexibility.

Virtualization

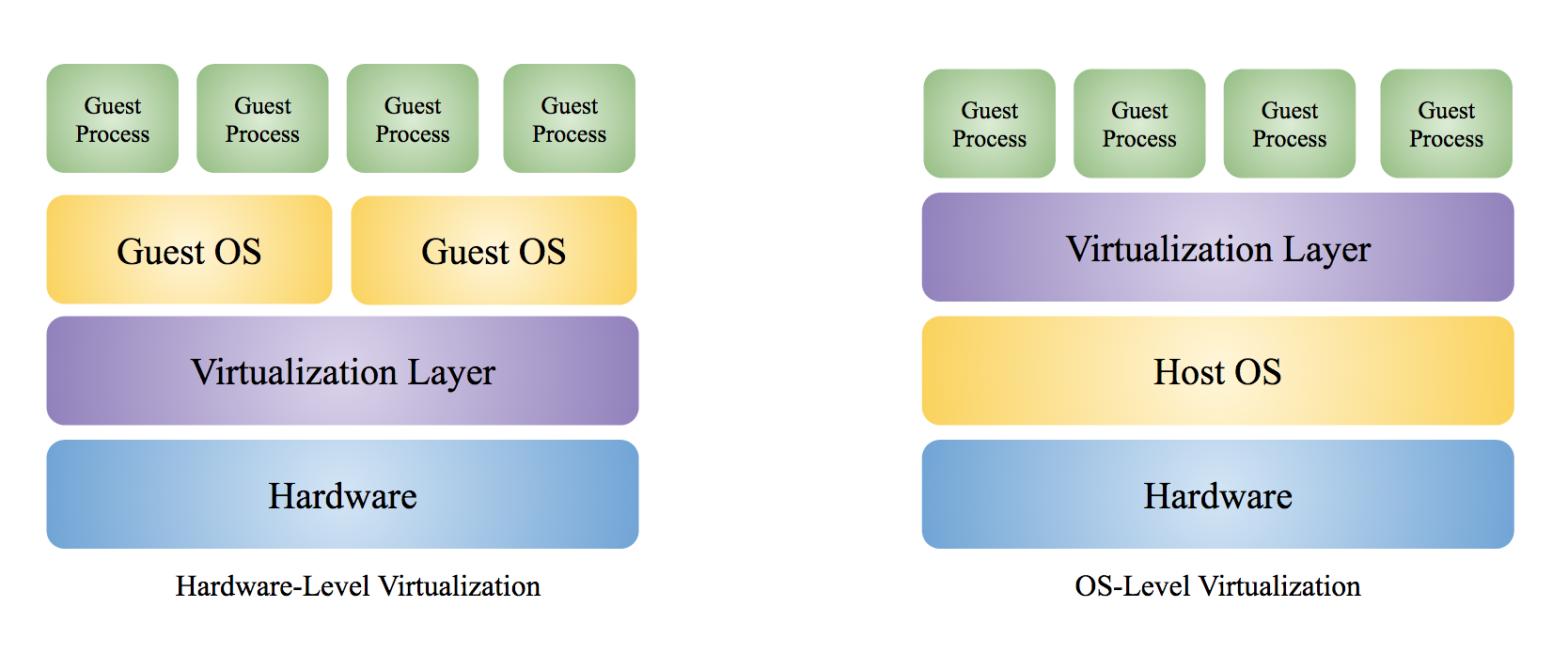

Virtualization introduces the concept of virtual machine (VM) by creating multiple execution environments (VMs) on a single physical machine while giving the illusion of a real machine, i.e., having its own resources (CPU, RAM, etc.). VMs are kept isolated from one other and the underlying physical machine. The obvious advantage of virtualization is the ability to run multiple VMs in one physical machine (server). Other benefits include easier migration of application from one physical machine to another with minimal downtime; lower cost of ownership, simulate hardware and run programs in incompatible OS environments, etc. To achieve the necessary partition among the physical machine and its VMs, a virtualization layer is introduced somewhere on the machine stack. The virtual layer can be at the hardware level, operating system level, or application level.

- Hardware level virtualization depends on a combination of emulation and direct execution of a guest OS instructions on the native CPU.

- OS-level virtualization partitions the VM and the host at the OS level. It redirects the I/O and system request from VM to host OS.

- Application level virtualization, for e.g. Java Virtual Machine (JVM), interprets binary code to native code.

The best isolation is achieved if the virtualization layer is closest to the hardware. However, it comes at the cost of higher resource requirements and flexibility. Though the isolation between the VMs and the physical OS decreases as the virtualization layer moves up the machine stack, it increases scalability and performance.

Hardware-Level Virtualization

In a hardware-level virtualization such as Type-1 Hypervisors, the virtualization layer runs on bare metal, i.e., without any host OS. The VMs run as user processes in user mode without the VM OSs aware of running in virtual kernel mode. When the guest OS executes a sensitive instruction (subset of privileged instruction), the virtualization layer intercepts (trap) the instruction and checks to see its origination. If the instruction has originated from the guest OS, the virtualization layer executes the instruction immediately. It emulates the behavior of the kernel or the hardware if the instruction came from a user program in the VM.

OS-Level Virtualization

For a OS-level virtualization, the virtualization layer runs on top of host OS. There is a few different ways on how the virtualization layer interacts with the VM and the underlying host OS.

Full VM

In a full featured OS-level virtualization, a VM can have its own guest OS which is completely independent from the host OS, e.g., Type-2 Hypervisors. The guest OS doesn’t share any kernel or libraries with the host OS. Type-2 Hypervisors uses a combination of binary translation and direct execution techniques to achieve the virtualization. The virtualization layer replaces the sensitive instructions in guest OS kernel code with new instructions (emulated) that have the intended effect on the virtual hardware. The guest OS doesn’t need any modification as the kernel instructions are replaced dynamically during the guest OS loading. Meanwhile, the user level code is directly executed by the virtualization layer on the host OS/processor. You can find more about hypervisor here.

OS Container

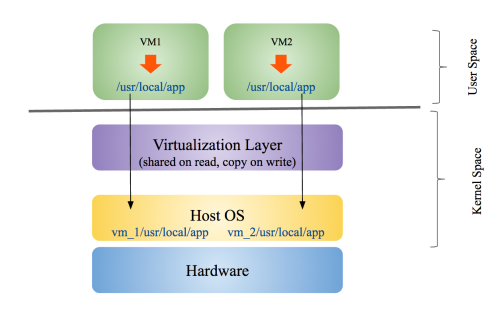

OS Container is another type of OS-level virtualization where multiples VM share a single host OS kernel. The VMs share the execution environment of the host but without any rights to modify them. Any changes to a VM, including any state or software changes, are confined to the VM’s local environment. This helps OS containers to have lower resource requirements and higher scalability.

OS container restricts the access request from a VM to the VM’s local resource partition. For example, if VM 1 tries to access /usr/local/app directory, the virtualization layer redirects the access to a directory named vm_1/usr/local/app on the physical machine. Similarly, the access by VM2 to /usr/local/app directory will be redirected to vm_2/usr/local/app directory. The redirection is transparent to the VMs and it is similar to chroot operation on Unix systems. The shared read resources are directly accessed by the VMs and they are not copied.

A prime example of OS container is LXC (Linux Containers). LXC introduced the concept of cgroups (control groups) that allows limitation and prioritization of host resources (CPU, memory, etc.), namespace isolation, etc.

Docker initially used LXC but later switched to Open Containers Initiative (OCI) specified container to avoid fragmentation in container ecosystem. A Docker container is is potentially switchable to another OCI based container, e.g., Windows Server Containers.

What is the difference between Docker and a full VM?

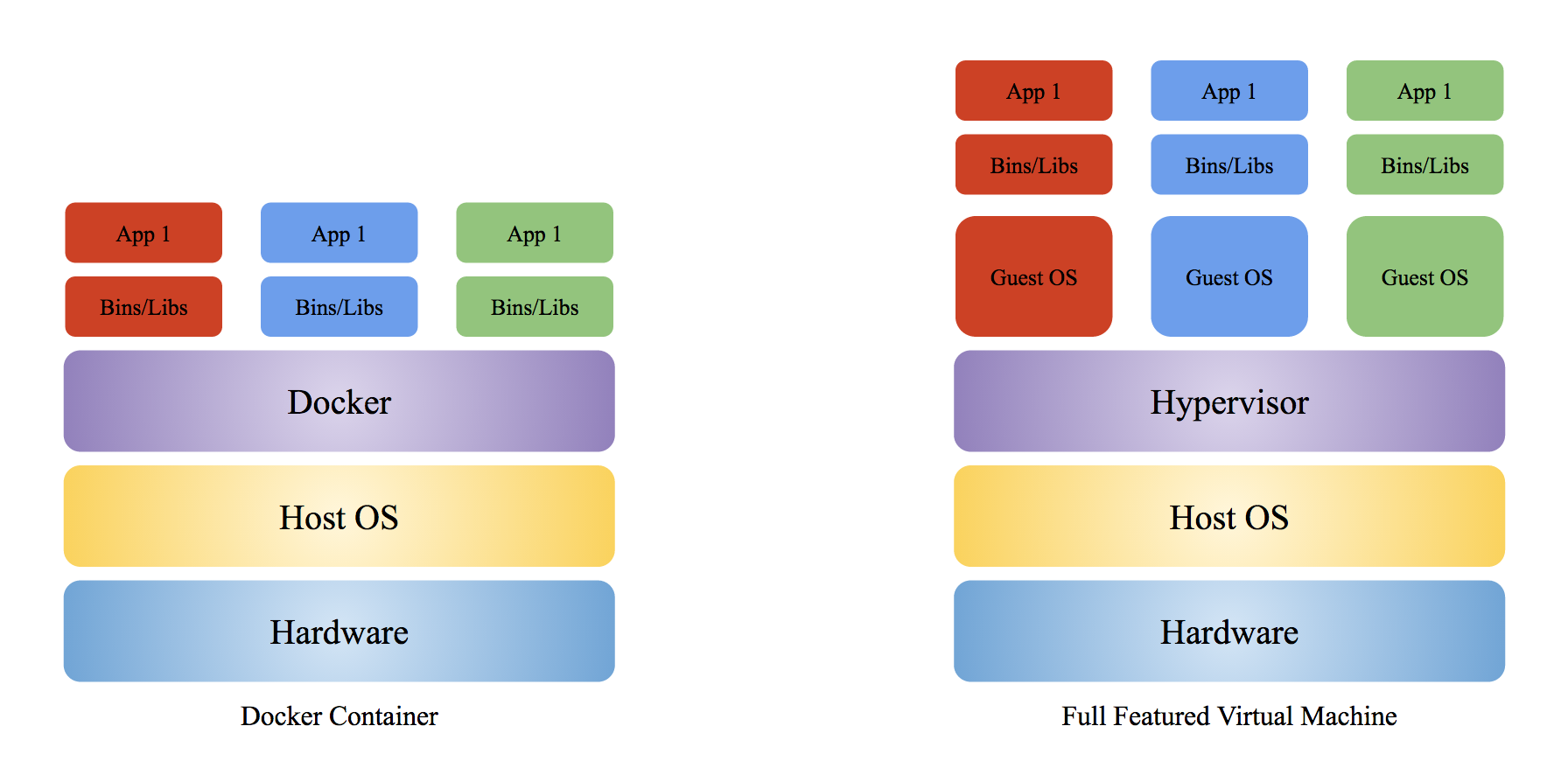

You will find a good answer to the above question in stackoverflow. Both Docker container and full featured VM like Hypervisor are OS-level virtualization but unlike Docker, a full VM doesn’t share kernel with host OS. This allows a full VM to run different OS on the same physical machine. Docker container sharing the host OS kernel prevents it from running an OS which is completely different from the container. For example, you will encounter errors (exception caught: unknown blob) if you try to create an image based on Windows OS or run a Windows based image on a Linux based Docker container. You can however create or run images based on different Linux distributions (distros) as they share the same kernel. To summarize, here are the pros and cons of Docker compare to a full VM:

Advantages

- Since a Docker container takes fewer resources, you can run many more containers on one physical machine. Lower cost of ownership. A full VM has it own resources and does minimal sharing.

- Docker containers share common read parts between them due to layered filesystem (more discussion later). So 1000 instances of a 1 GB Docker container image will take much less space than 1 Terabyte (1000 GB).

- Faster startup time in the range of seconds compared to several minutes for a full VM.

- Easy to deploy.

Disadvantages

- Less isolation.

- Cannot run a completely different OS than the container OS.

Docker Architecture

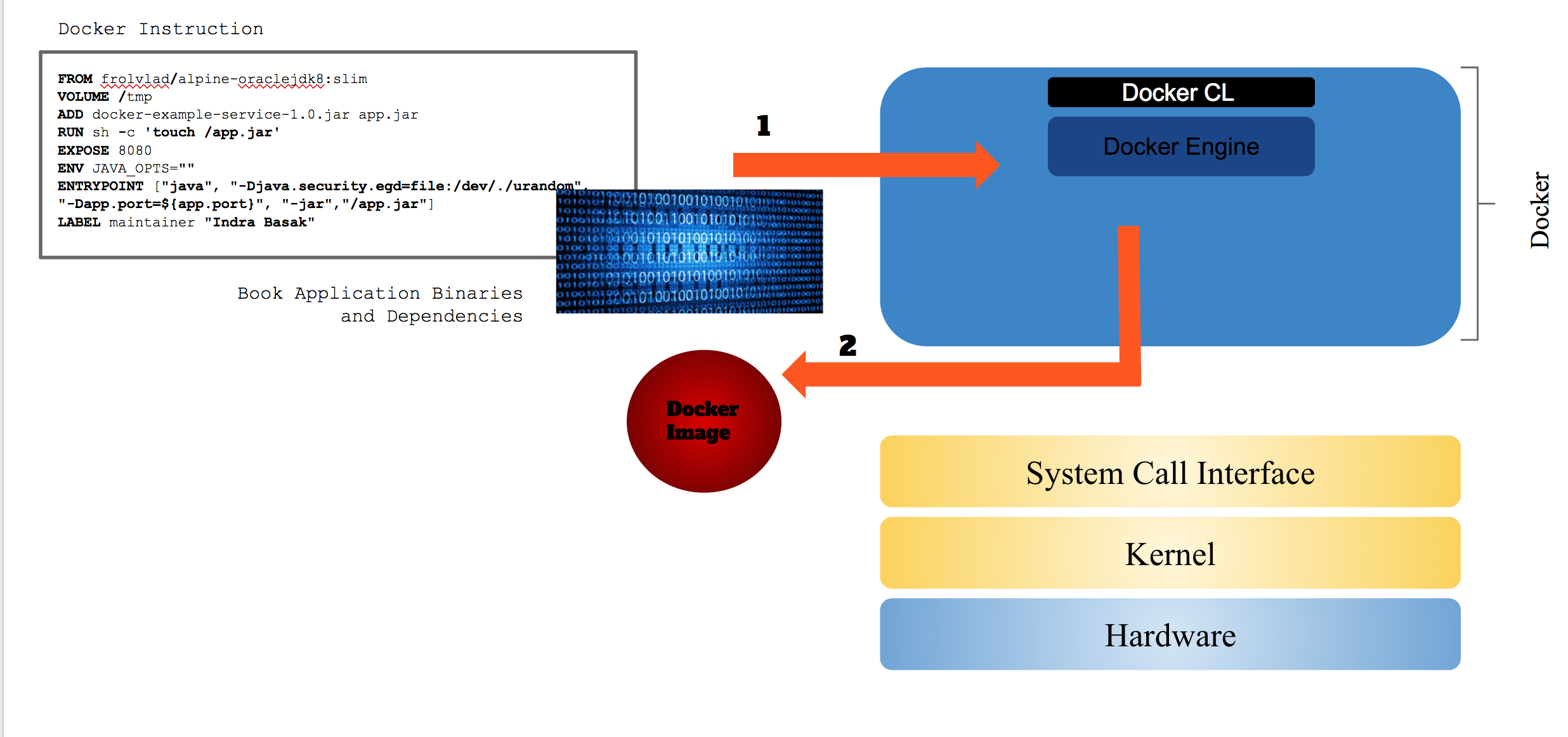

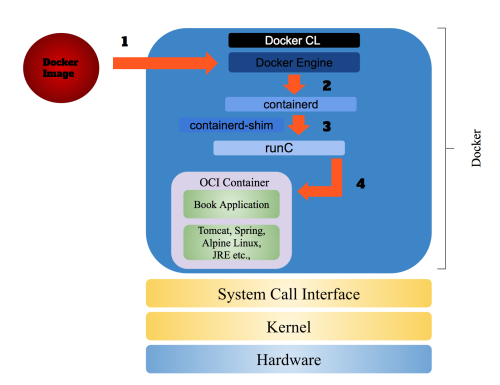

To get a better understanding of Docker, we should get familiar with the main components of the Docker. Here are the main parts of Docker: Docker Engine is the main entry point of Docker. It is responsible for building the Docker image, orchestration, managing volumes, networking, scaling, etc .

Docker Command Line (CL) is the command line utility for interacting with Docker.

Once you request Docker Engine to run an image, it delegates the responsibility to the containerd daemon. containerd takes care of downloading (transferring) and storing the container image; creating the root filesystem and calling the runC via container-shim to start the container; supervise the container; manage low-level storage and network interfaces.

gRPC is the communication protocol used between containerd and Docker Engine.

The runC is the process responsible for creating and starting the container, i.e., container’s runtime. It’s built on libcontainer. Once runC receives the image and configuration from the container-shim, it spawns and initializes the container as its child process. Once the container starts, it handles the responsibility of managing the container to the container-shim before exiting. The configuration contains all the required information to create a container.

To view runtimes of your Docker host can be viewed by typing docker info|grep -i runtime. You can see the following output:

$ docker info|grep -i runtime Runtimes: runc Default Runtime: runc

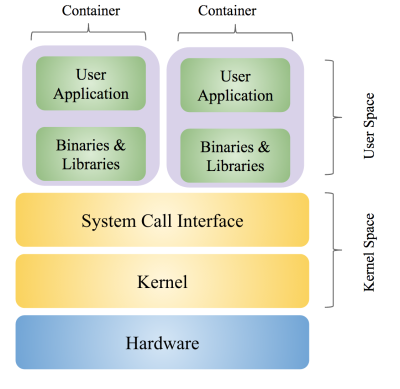

The container-shim manages the headless containers after the exit of runC. The Docker container is based on Open Containers Initiative (OCI) runtime specification. Within a container, an application runs in isolation without affecting the OS resources (CPU, memory, disk, network, etc.) of the host and other containers. Since a container runs on the same operating system as its host, it shares a lot of the host OS resources. This allows the container to have minimal operating system (without the kernel, system call interface, drivers, etc.) necessary to run an application.

The Docker container uses a layered filesystem called AuFS. AuFS has read and write parts. The common read parts are shared across different containers while maintaining a separate write mount for each container.

Docker Image

Running your application in Docker starts with building a Docker image which is the building block for an application. A Docker image is a tar archive containing all the files, libraries, binaries, and instructions required to run your application.

Docker images are built as layers. Let’s consider the Docker image from our previous example. We can see the history of the example image by typing docker history docker-example on the terminal.

The final image docker-example consists of eleven intermediate images. The first two layers belong to the alpine Linux base image and the rest belongs to instructions in the example Dockerfile.

To see the benefits of layering, let’s try to build another image with a slightly different name, docker-example-hello, but with the same Dockerfile. Now let’s take a history of the docker-example-hello:

You can see the first five layers of the new image is same as the docker-example. Since docker-example had created the intermediate layers of alpine Linux and tmp folder earlier, the new image reuses those layers. You will also notice the build process is faster than the previous image build. The images in your local computer, which in my case is a Mac, are usually stored in the following directory:

/$HOME/Library/Containers/com.docker.docker/Data/com.docker.driver.amd64-linux/Docker.qcow2

Running an Application in Docker

Once Docker receives a request to run a Docker image, the Docker Engine delegates the responsibility to the containerd. containerd downloads or transfers the image from the repository and stores the image. It creates the root filesystem before calling the container-shim with the container configuration. The container-shim relies on runC to create and initialize the container. Once the container is initialized, runC exits to allow for daemon-less containers. The remaining lifecycle of the container is managed by containerd via container-shim. There is one container-shim per container.

Once your application is running, you can view your container by typing typing docker ps. You can see the following output:

If you want to see the content of your Docker container, docker-example, you can view it by typing docker export command:

$ docker export cheetos | tar -xv x .dockerenv x app.jar x bin/ x bin/ash x bin/base64 x bin/bbconfig x bin/busybox x bin/cat x bin/catv x bin/chgrp x bin/chmod

Here is the first level directory structure of the example application container content using tree command:

tree -L 1 content/

content/

├── app.jar

├── bin

├── dev

├── etc

├── home

├── lib

├── lib64

├── media

├── mnt

├── proc

├── root

├── run

├── sbin

├── srv

├── sys

├── tmp

├── usr

└── var

I hope I was able to broaden your understanding of Docker with this posting. Docker is still in its infancy and it is rapidly changing with every release. What holds true today about Docker might not hold tomorrow.